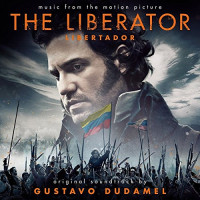

- Composed by Gustavo Dudamel

- Deutsche Grammophon / 2014 / 54m

I’ve been thinking through what I consider to be the great achievements of my life – that time I assembled an Ikea wardrobe all by myself in just seven hours, or when I fixed the burglar alarm without needing to call out an electrician, or when I came second in the table tennis competition at the hotel when on honeymoon – and I will be the first to admit that this roster of notable successes is perhaps not quite on the level of Simón Bolívar (or, to give him his full name, Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios Ponte y Blanco – try saying that after a couple of pints of Carling). Had his only achievement been liberating Venezuela from the Spanish then I guess I’d have nothing to worry about, but the fact that after doing that he went on to do the same thing for Colombia, Panama, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia (which is even named after him) means he just edges ahead of me when it comes to notable people.

His remarkable life certainly seems ideal for a movie treatment and it has arrived in the form of The Liberator, a Spanish/Venezuelan co-production directed by Alberto Arvelo. Superstar conductor Gustavo Dudamel – who hails from Venezuela and is best-known for his role as principal conductor of the Orquesta Sinfónica Simón Bolívar – was initially hired as a musical consultant to the film, but ended up taking a rare venture into composition, writing his first (and, according to him, last) film score, reportedly taking on advice from his friend John Williams (you may have heard of him) in the process. And what a debut it is – cultured, elegant and colourful. And it’s not really like what usually happens when someone from the classical world crosses over into film music and writes impeccably-crafted but perhaps dramatically suspect music (that receives great acclaim and many awards) – for better or worse, this sounds like a film score and has all the dramatic sweep a film like The Liberator demands.

The album opens with “Quien Puede Detener la Lluvia?” and one of its most striking features is immediately evident – the beautifully expressive writing for woodwinds and the beautifully expressive playing. It’s plaintive to begin with – a rumination, an impression of serenity – before first tribal percussion and then an expansive horn theme and finally a faintly liturgical choir join in – if I say it’s half way Ennio Morricone (The Mission) and half way James Horner (Avatar) then you get the idea. I should qualify that by saying that the melody isn’t as memorable as either, but it’s still a knockout, an arresting and powerful way to start the score.

Some action music arrives in the next cue, “El 25 de Septiembre de 1828” – a pounding section of sweep from the whole orchestra – surrounded by some more intricately detailed wind writing and the subtle colour of a guitar. In “Regreso a Venezuela”, a very delicate theme is revealed, lilting and tender; and the striking bursts from pan pipes are again reminiscent of both Morricone and Horner. It’s interesting just how filmic the music is – like the best of those two master film composers, it is musically fully-formed (as one would expect) but with the unmistakable narrative drive that is probably the thing that makes film music so attractive to that small group of us who love it.

“María Teresa” (presumably not named after the one from Calcutta, who I don’t think had much bearing on Bolívar’s life) is an emotional powerhouse, seven minutes of conflicting feelings presented (very deliberately, one presumes) in the most serene of ways, opportunities for various soloists to bring something to the table, punctuated by passages for the full orchestra. It’s very moving, impassioned and colourful without ever being remotely overbearing, a rare skill. Much sunnier is the delightful little vignette “Paris”, full of the joys of spring; and then the romantic “Fanny du Villars”, a gorgeous melody being passed between oboe and flute.

A strained, ominous feeling opens “La Caída de la República” but it closes with a noble trumpet solo a little reminiscent of Williams’s three scores for Oliver Stone. “Destierro a Cartagena” has more of those evocative ethnic flutes, combining with subtle percussion to give a real sense of forward motion, though subtlety is abandoned for the closing stages of the piece as the pace becomes more ferocious. The moving main theme introduced earlier in the score is heard again in “Esto No Es Una Frontera, Esto Es Un Río”, heard this time in a more contemplative – but no less haunting – setting. There is an air of tragedy to the piece, an air only exacerbated in the following “Jamaica”, a feeling of desperation growing through as it progresses. The growing darkness turns thrilling in the action-laden “Angostura”, strings stabbing the now-familiar bed of winds and percussion before an explosion of brass to conclude the piece.

Something of a turning point is reached in “El Paso de los Andes”, a piece positively flowing with cautious optimism, enhanced by some beautiful choral sounds. “Ellos Están Con Nosotros” begins with a passage of undiluted beauty from the a capella choir, then after a note of caution is introduced through some tense orchestral strains the sun rises once again. “Boyacá” is an action track with a difference, an unmistakable sense of hardship running through the cue – in stunning contrast to the exceptional “Muere el Mariscal” which follows, featuring a haunting choir boy solo. In “Manuela” emotion again floods to the fore, anguished but beautiful; then comes the excellent finale “El Último Viaje” featuring the most powerful statement of the main theme in the whole score.

The Liberator may not be the kind of score that provides the kind of instant gratification my gushing words above may suggest. It has real depth to it which rewards the patient listener as new details are revealed. It is incredibly intricate music, full of passion but absolutely not overwrought – Dudamel makes the listener do some of the work, make some of the leaps required, and that’s no bad thing at all. The score’s charms may not be instantly apparent (though the beauty of the composition and performance will be) – spend the time with the score to really get to know it and I would expect that most people, like me, will completely fall under its spell. This is intelligent, emotional music which makes as arresting a début film score as I can remember in a very long time.

Rating: *****

facebook.com/moviewave | twitter.com/MovieWaveDotNet | amazon.com

sorry, james, but this time i don´t agree with you. all that comes along with the opening track is so badly predictable and so often been heard in the past. for the entire score, it´s quite nice to listen to, not more, not less.

and apart from that I hope that you’ll listen to paolo buonvinos “padre pio” at some point, that´s a real gem and breathtakingly beautiful! i do really hope you will!

best regards, dominique.

hmmmmm – it´s an OK score but not 5 stars – no real higlights – too much Hornerism and Williams influence, but the music creates a good atmosphere

***1/2 I´d say

For me, this is an excellent score. Gustavo Dudamel is a real talented composer, and I hope he does not fulfill his promise of writing no more film scores.