Wes Craven’s Deadly Blessing was about the only one of his first few films that didn’t go on to become a cult favourite – ironic, given it’s about a cult (well, kind of). A man is murdered after he decides to leave his Amish-type community to marry; his wife and her friends are then left in the middle of all sorts of satanic goings on.

James Horner rarely dabbled in the horror genre once he established himself, but in 1981 – when he was only 27 – three of the four films he scored were horrors, with this one sitting in between The Hand and Wolfen. The filmmakers wanted him to make it sound like The Omen and to some extent he did, though given his notoriety in that regard – and in particular his obvious admiration for Jerry Goldsmith at the time – not nearly as much as some may suggest.

You can hear the mild Goldsmith influence in the first track – some chants of “morte” rather than “ave satani” – but these are used to provide contrast to a surprisingly lilting, lovely melodic theme. Not long later we get an even more sweeping piece, “Martha and Jim” which is typical of early-career Horner love themes – unabashedly romantic, complex layered strings, it’s absolutely lovely.

This is a misleading start to the score however because it swiftly turns into a suspenseful nightmare of a piece – while there are occasional choral passages these are generally much more subtle than those in The Omen, the chants feeling part of a wider thing rather than the centrepiece – however Horner does follow the same Stravinsky-cum-Bartok route as Goldsmith did in his masterpiece for the orchestral passages. In general Horner’s music is much more psychological in nature – showing admirable restraint he mixes unsettling strings with percussion and low-end piano as he ratchets up the tension. In “Gluntz’s Demise” he builds and builds this style before suddenly unleashing larger forces – and when he does that it has a chilling effect. It’s impressive how many different ways Horner finds to use his string section to pile it all on – towards the end of “Snake in the Bath”, rather than a predictable stinger the composer suddenly unleashes a thrilling little passage of excitement.

I love “Trouble in the Convertible”, which admittedly is a completely blatant Omen rewrite – they do become more prominent in the score’s later sections. The dynamic shrieked chanting is just great, played off against pounding orchestral action. In “Faith Leaps Out” we get a great preview of some material that would be refined and developed not long later in Star Trek II.

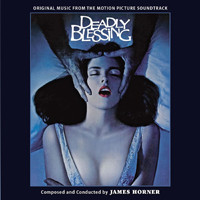

Until Intrada’s 2023 release, Deadly Blessing was one of the very few completely unreleased Horner scores. Apparently he did prepare an album at the time but lost interest in releasing it when the film performed poorly. While it’s not a classic by any means, there was always something exciting in the composer’s early scores and this is certainly no exception – as a great fan of the composer I always love hearing the early formative versions of tricks and techniques he would develop in the decades to come. One word of warning is that the sound quality is pretty ropey at times – not to the point of rendering it unlistenable, but audiophiles will be uncomfortable.

You never stop surprising me, James. Will we get a summer round-up soon as well?